Explore the evolution of Hamnett Pinhey’s great house and its restoration in the 1990s.

The House | Restoration 1995-1996

The House

Horaceville, the residence of the Hon. Hamnett Pinhey, was named for Pinhey’s eldest son Horace, who, in keeping with British gentry practice, was intended to be the heir to the property.

The house was built in four stages, from north to south.

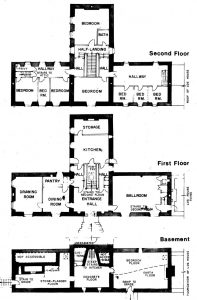

The original house, built in 1820-1821, was (according to the Earl of Dalhousie, an early visitor) “a nice tasty cottage with viranda [sic]”. It was a two-storey log building, covered with clapboard. To the rear was a square stone kitchen with hip roof.

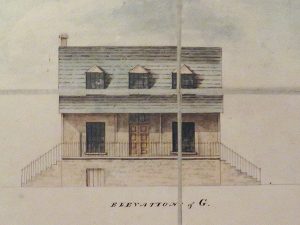

From 1822-25 a stone parlour wing was added. Upstairs were three small bedrooms, probably servants’ quarters, opening off a wide hallway-sitting room. The house is pictured at this stage of development in a rare print of a sketch done by Mary Anne Pinhey in the 1830s.

In 1841, Pinhey began to look ahead to the day Horace would marry and take over the farm. He planned a large addition in two stages.

The central hall-kitchen wing was built in 1841-42, with a gracious sweeping staircase leading upstairs to a dining room at the head of the stairs and a bedroom over the front entrance.

The new kitchen wing to the rear was to become Mrs. Pinhey’s kitchen when a daughter-in-law took over the older part of the house.

On August 21, 1847, Horace Pinhey married Kate Greene at neighbouring St. Mary’s Church, and in September work began to enlarge the old stone kitchen to better serve the young couple.

In 1848-49 the final, south wing was added, including a library, pantry, and drawing room on the ground floor. Upstairs, several bedrooms and an interesting second-storey privy, which Pinhey called the “sanctum sanctorum”, Latin for “the holy of holies”, were added.

Horace and Kate moved into the older part of the house and took over management of the farm, turning over half the produce each year to his parents. Hamnett retained control of the gardens and moved with wife Mary Anne and daughter Constance into the newer part of the house.

At Hamnett Pinhey’s death in 1857 he willed the new half of the house to daughter Constance. However, she married her cousin John Hamnett Pinhey and moved to town shortly thereafter, deeding her inheritance to Horace. Horace’s son Hamnett Pinhey II assumed ownership of the house upon Horace’s death in 1875.

In the nineteenth century, the Pinhey house had been expanded to accommodate a growing family. After the First World War, it was home to an aging family. Hamnett II died in 1941. His son Horace II and his resident sisters of the fourth generation never married.

The family rejected proposals to make Horaceville the home of a Hollywood actress or a summer residence for the Governor General. Horaceville remained the Pinhey family farm until the 1970s. In the early 1970s the remains of the log cottage collapsed. The stone kitchen behind was partially dismantled for safety reasons and the ruin was stabilized.

In the end, Miss Ruth Pinhey alone occupied the deteriorating central wing of her ancestors’ great house. She died in 1971.

Restoration 1995-1996

The City of Kanata (now part of the City of Ottawa) assumed ownership of the Pinhey property in 1990 and commissioned renowned conservation architect Julian Smith to prepare a Master Plan Study to improve the old house. In 1993 Smith presented Kanata with several options: period restoration, rehabilitation—modification for contemporary uses, and minimal intervention. The City opted for a compromise: to alter the building as little as possible, but to upgrade it for contemporary functions in a way that reflects its original appearance. This work protects the house from further wintertime deterioration and makes it occasionally usable out of season.

Phase I and II

Assisted by funding from the federal/provincial Infrastructure Program, the long-awaited restoration of the Hamnett Pinhey mansion began in January 1995.

The first two phases included the installation of furnaces, heating ducts, air conditioning, electrical outlets, and plumbing.

Five propane furnaces were installed, one in each of the attics and one in the basement of each of the side wings. With the heating system in place the cellar was drier than it had been in many a year. Visitors long familiar with the property may recall the veritable torrents of water that flowed down the slope of the hill, through the cellar and out again, especially in spring. The cedar log floor beams no longer dripped condensation.

The new electrical outlets, including brass floor outlets, provided greater flexibility in lighting displays in the house.

The mid-20th century washroom that had intruded into the upstairs dining room from the landing at the head of the main staircase was removed.

Three new washrooms were added: two in the southeastern cross passage on the ground floor to the left of the stairs, and one, a staff washroom, in the front half of the first bedroom in the east wing.

New discoveries in the kitchen were most exciting to the historically minded. Previously blocked up, the great stone fireplace was opened and restored. The 1920s v-groove woodwork was stripped away, as was some of the lathed ceiling, to reveal the hand-hewn ceiling beams. Markings on the floor, and the only partial covering of the ceiling with lath-work, revealed that the two exterior doors that open into either side of the kitchen wing originally opened into a cross passage, and that two doors formerly gave ingress into the kitchen from this passage. Given the severity of Ottawa winters this arrangement was eminently sensible, but previously undocumented. This passage was restored.

The rear half of the kitchen rests upon bedrock. Some of the original flooring, laid parallel with the side walls, remains in the front half of the kitchen and former passage. However, much of this flooring had long ago been replaced with floorboards that ran diagonally throughout the room.

The cornice in the drawing room was of very recent vintage, installed to replace the original plasterwork which was fracturing and falling away. This was replaced to match the mouldings in adjoining rooms.

The open stair at the end of the second-floor sitting room above the ballroom (parlour) was enclosed with a fire wall to meet fire code, although the railing has been retained within the staircase. The new door replicates the originals elsewhere in the room, but the moldings have been simplified so that it character as a reproduction would be obvious on close inspection.

Phase III of the restoration of Horaceville began in January 1996. Included in this stage of the project were non-structural repairs, plastering, painting, lighting, and installing picture rails. Installation of the picture rails, requested by the Pinhey’s Point Foundation, facilitates displays in the parlour (ballroom), the dining room, and the room over the front entrance. Some external work, such as improving the flashing on the crest of the roof, was also completed.

Architect Larry Gaines of Julian Smith and Associates carefully selected the internal finishes by comparing the paints available from heritage supply companies with Deborah Hossack’s study of the historic finishes in the Pinhey house, commissioned some years ago by the Foundation. Attention to authenticity and detail is a hallmark of the work that has given Julian Smith and Associates a deserved reputation as one of the most respected firms of restoration architects in Canada.

Also in this phase, the original windows and shutters were put back in place where possible. Interestingly, it was discovered that the shutters were interior, which are far more practical, rather than exterior. Interior shutters are still to be found flanking the windows in the landing at the top of the main stair, but the presence of door-length jalousies (sham shutters) attached to the wings of the house for purposes of symmetry, along with Pinhey’s diary references to jalousies and shutters, had given the misimpression that most of the shutters were outside.